This new blog series explores the problematic history of the Type A personality in two parts.

‘Type A’ referred to people who were ambitious, aggressive, and extremely competitive. They were always short in time and in constant pursuit of achievements. In the 1970s and 1980s, a stream of news articles and scientific reports stated that people with Type A behavior had an increased risk of coronary heart disease. Bestseller books explained to readers how they could “liberate” themselves of this risk if they were willing to recognize and change their personality flaws. An article in the New York Times advised Type A’s to “practice standing in lines doing nothing.”

Later scientific studies failed to replicate Type A behavior as a risk factor for heart disease. Eventually, it would become clear that much of the original research had been secretly funded by the tobacco industry. In part I we looked at the rise of Type A and how it entered popular culture. Today, in part II we dissect the strategy of cigarette companies in promoting psychosomatic research to cast doubt on the relationship between smoking and heart disease.

Tobacco funding

Because of multiple lawsuits in the 1990s, big tobacco companies were obliged to make some of their internal documents public. These revealed how the industry funded questionable science with the intent of casting doubt on the relationship between smoking and illnesses such as cancer and heart disease. An analysis by Mark Petticrew and colleagues from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine exposed how research on Type A behavior fitted into this strategy.

One document from Philip Morris, for example, explained: “It is clear the really large potential for shifting blame away from smoking lies with the prospects for a growing appreciation of the role of the psychosocial factors.” Another document stated: “I think our only significant hope of exoneration lies in proving, that people die early primarily because of their personality characteristics.”

The industry obviously wanted to drive attention away from smoking to other possible causes of heart disease but there was another element to their strategy. In essence, they wanted a confounder: a personality characteristic that correlated both with smoking and heart disease so that adding it to a statistical regression would make the relationship between smoking and heart disease go away.

Once a couple of papers asserted a relationship between this personality characteristic and heart disease, the industry could argue that all previous studies indicting cigarette smoke were flawed. They could claim that these studies failed to control for all risk factors because this new personality feature was not yet taken into account.

This is the reason why big tobacco companies saw great potential in Type A behavior and why they were so generous in funding the studies by Friedman and Rosenman. One internal document explained:

“… success for the Friedman project will have a strong tendency to discredit the major prospective mortality studies that appear to indict smoking; but fail to discover, and adjust for, a very large effect on mortality from negative mental states.”

Other documents reiterated this strategy:

“… the tobacco industry could argue that studies that fail to consider and control for Type A behavior are confounded and that the actual risks associated with smoking must be lower than reported.”

This is basically what happened. When the iconic Framingham study lost its government funding, tobacco companies stepped in as new funders so that they could get hold of the data. Industry consultant Carl Seltzer published a reanalysis where the association between smoking and coronary heart disease disappeared when Type A behavior was taken into account.

The crown jewel

The support for Friedman and Rosenman totaled millions of dollars. Although the two cardiologists acknowledged a link between smoking and heart disease in their book, they made controversial statements elsewhere. In a 1976 interview with the Los Angeles Times, for example, Rosenman stated: “We have no convincing evidence that cigaret smoking triggers coronary events.” Rosenman also participated in “The answer we seek”, a dubious film created by the Tobacco Institute to cast doubt on the relationship between smoking and disease.

Friedman wrote a letter to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) as it assessed the evidence on smoking and cardiovascular disease in 1994. Friedman stressed that the evidence reviewed was useless because it didn’t account for Type A behavior. The tobacco industry also used a statement by Friedman from 1961 as one of their selected quotations. It read:

“It seems probable that heavy cigarette smokers have more clinical coronary artery disease than non-smokers. Does this mean that excess nicotine is responsible? Or does it mean that persons exhibiting the behavior pattern I described above tend to smoke more? In other words, are we mistaking a concomitant for a cause? I am positive we are, not only by our own studies on this subject but also by the application of some solid common sense.”

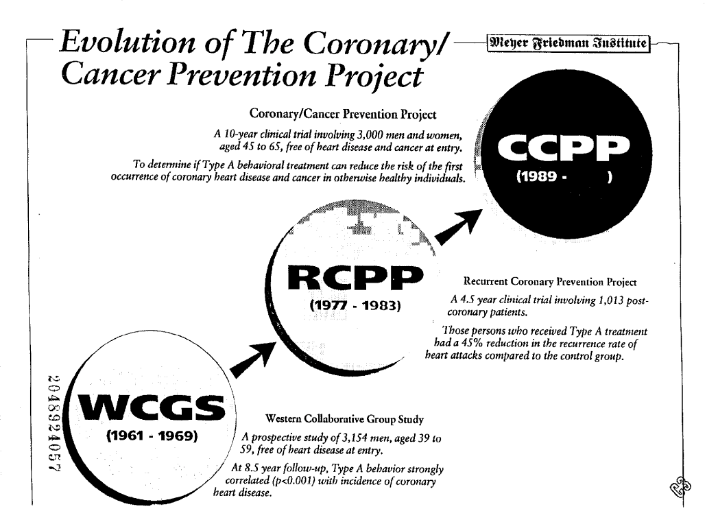

Friedman created his own institute – the Meyer Friedman Institute – which received more than 10 million dollars from the tobacco industry for various studies. It also acted as an intermediary of tobacco funding for scientists and institutions who needed to hide its source.

The biggest study – which internal documents describe as the “crown jewel” of the program – was the Coronary/Cancer Prevention Project. Philip Morris spent millions on this study alone. It was supposed to show that treating Type A behavior in healthy individuals reduced the incidence of coronary heart disease and cancer. Despite large sums of funding, spanning multiple years, the results of the study seem to have never seen the light of day. It is unclear if it was ever finished. It planned to recruit 3000 participants and follow them over a period of 10 years.

Anger Kills

When the esteem of Type A behavior as a risk factor dwindled, researchers looked for subcomponents that might have more success in predicting heart disease. Hostility was identified as the most promising one. The first and most prominent proponent of this view was Redford Williams, Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University.

Together with his wife, he wrote a book called “Anger kills: strategies for controlling the hostility that can harm your health.” The main message was that 20 percent of the general population had levels of hostility high enough to be dangerous to their health. Williams wrote that such hostile persons were “at higher risk of developing life-threatening illness.” Much like Friedman and Rosenman did in their book on Type A, Williams offered its readers strategies to keep their hostility in check. One piece of advice was to keep a hostility log where readers could write down situations in which they experienced aggressive feelings. The book also advised: “When you become aware of having a hostile attitude or thought, shout ‘at’ it to ‘Stop!’”

Another promoter of hostility as a risk factor for heart disease was Lynda Powell, a professor at Yale University. In an interview with the New York Times, she explained:

“Hostility and cynical mistrust are consistently associated with coronary artery disease. The constant ongoing vigilence associated with being mistrustful appears to promote coronary heart disease by speeding up the deposition on the atherosclerotic plaques on the walls of the arteries.”

The evidence was by far not as strong as Powell suggested. Much like the research on Type A behavior, the connection between hostility and cardiovascular disease failed to replicate.

Research on hostility also received funding from the tobacco industry. Philip Morris supported Williams with a budget of 5 million dollars for a period of four years starting in 1985. The goal was to create a “Behavioral Medicine Research Center” at Duke University that would investigate psychological features such as hostility as risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Powell solicited funding from R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company (but it seems her proposal was denied). She also received smaller checks from Philip Morris which were channeled through the Meyer Friedman Institute.

Type D personality

There is one last chapter to the story. Although there were no tobacco dollars involved (as far as we know), the storyline is much the same as before.

In the 1990s Belgian psychologist Johan Denollet came up with a new personality type that he believed to predict heart disease mortality. Instead of Type A, it was called Type D personality, the D standing for ‘depressed’.

Type D personality was a combination of two things: a tendency to experience negative emotions such as worrying or feeling depressed on the one hand, and social withdrawal with inhibited self-expression on the other. Denollet combined two existing questionnaires and noted that patients scoring high on both scales were more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than others. As such the Type D personality was born. By giving it a catchy name, the idea immediately became popular.

Denollet was able to publish his preliminary findings in The Lancet in 1996. Even though the paper presented data on only 24 cardiovascular deaths, it would be cited almost a thousand times. The media followed suit. Articles appeared explaining “Why Type D personality is important, but often overlooked.” “Are you the shy and retiring type?”, the Times asked, “If so, watch your heart.” The article mentioned fictional donkey and Winnie de Pooh character Eeyore as an example of a Type D personality. Time Magazine ran a piece titled: “Are You a Type D Personality? Your Heart May Be at Risk”. In it, Denollet explained that psychological treatment might benefit patients with a Type D personality.“Helping them address their sources of anxiety”, he said, “through counseling or active intervention to change whatever may be causing them stress, can help them brighten their negative outlook.”

The evidence on Type D personality consisted of small studies and most were from the research team of Denollet. Some had more variables in their statistical analysis than cardiac deaths to be explained. Others reported effect sizes that were unrealistically large. In the Lancet paper, for example, Type D patients were four times more likely to die of heart disease than controls. When larger studies were conducted by independent research teams, the relationship between Type D personality and cardiac death disappeared.

Current situation

The stories about Type A and Type D personalities demonstrate how strongly people like to believe that psychological factors influence heart disease. But where does that leave us today?

Current evidence suggests that psychosocial factors such as stress may influence the incidence of heart disease but that the effect size is lower than for traditional risk factors such as cholesterol or hypertension. Most of the data comes from observational studies, so it remains unclear if there is a true causal relationship. Another plausible explanation is that psychosocial stress is only correlated with other risk factors that are not yet identified or fully accounted for.

Experimental data from randomized controlled trials can provide clues to the correct answer. Friedman and Rosenman conducted a big, randomized trial called the Recurrent Coronary Prevention Project. It found that psychotherapy to change Type A behavior resulted in a notable reduction of cardiovascular disease. The results played an important part in the initial acceptance of Type A behavior as a risk factor but have never been replicated since. A 2017 Cochrane review of 35 trials reported that psychological interventions lead to a small reduction in cardiovascular mortality but the quality of evidence was low. It also noted that there is “no evidence that psychological treatments had an effect on total mortality, the risk of revascularisation procedures, or on the rate of non-fatal MI [myocardial infarction].”

The biggest study to date is likely the ENRICHD trial, published in 2003. It focused on depression and low perceived social support, two prognostic factors that have been at the center of psychosomatic research on heart disease in recent years. The ENRICHD trial randomized 2481 heart disease patients to receive either usual care or cognitive behavior therapy with antidepressants. While the intervention improved depression and perceived social isolation, there was no parallel benefit on cardiac mortality and recurrent infarction. Although the trial had its limitations, it suggested that depression and low social support are not causally related to the prognosis of heart disease.

Some have noted how the coronary-prone personality has changed as heart disease progressed through socioeconomic strata. From the Type A personality that dominated aggressively and tried to control everything, it ironically shifted into a Type D that lacked control over its circumstances and withdrew from social events. While Type A was doing too much, Type D was depressed. This reversal in descriptions of psychological risk factors, suggests that they are more likely to be confounders than causes of heart disease.

A news article from 2001 shows how times have changed. Dick Cheney, at the time Vice-President of the US and someone who would fit any Type A personality description quite well, underwent a surgical procedure to clear a blocked coronary artery. He had already had 4 heart attacks at the age of 60. The New York Times raised the question if the stress and long working hours his position required, had contributed to his poor health. Twenty years earlier this question might have been answered affirmatively, but now the experts who weighed in, dispelled the idea. Dr. Eugene Braunwald from Harvard University explained that he had reviewed data from the last four decades and ”was not very impressed with firm evidence for stress-related progression of coronary disease.” The American Heart Association also responded: “Stress management is an appealing concept and makes sense for a person’s overall health. However, the available data do not yet support specific recommendations for its use as a proven therapy for cardiovascular disease.”

Our next blog post will explore the dark psychosomatic history of rheumatoid arthritis. Stay tuned.

Thanks for your careful work – it makes me so angry to see the deliberate misuse of science.

This could be turned into a book. It would really signal that people need to be careful when psychological causes are attributed to a disease.

Thanks for the suggestion Barbara. We first try to keep writing these stories because there are a lot more than needs to be told. Because of our illness, it takes quite a long time to go through each of these. Afterwards we will see how the whole blog series could be grouped into one storyline.