Few illnesses have faced such persistent and damaging stigma as epilepsy. People with the illness were once thought to be possessed by evil spirits or witchcraft. In the early 20th century a psychoanalytic view emerged that saw epileptic seizures as a ‘flight into unconsciousness’. Promoted by the American psychiatrist Leon Pierce Clark, this theory states that people with epilepsy are egocentric and infantile and when they are no longer able to face disappointments and difficulties in the real world, they retreat from reality in the form of a seizure. Today, this psychoanalytic side-turn is regarded as an embarrassing mistake in the scientific study of epilepsy.

Karen Armstrong

Karen Armstrong, the British author known for her popular books on religion, struggled many years with frightening symptoms before she finally received a diagnosis of epilepsy. She had medically unexplained blackouts and hallucinations. “I was in and out of mental hospitals and I went to a fleet of psychiatrists, who also thought I was neurotic”, Armstrong said in an interview with Oprah Winfrey.

Armstrong explained that the day she was diagnosed with epilepsy was probably one of the happiest in her life. “For years I had feared that I was losing my mind and would end my days locked in a psychiatric ward”, she wrote in an opinion piece in the Guardian. “When – finally – I was told that I was not mentally ill but had a neurological condition that could be successfully treated with drugs, it was a relief and a delight. I learned that my symptoms had been caused by an injury to the brain’s temporal lobe, which controls memory, and that I was not a freak.”

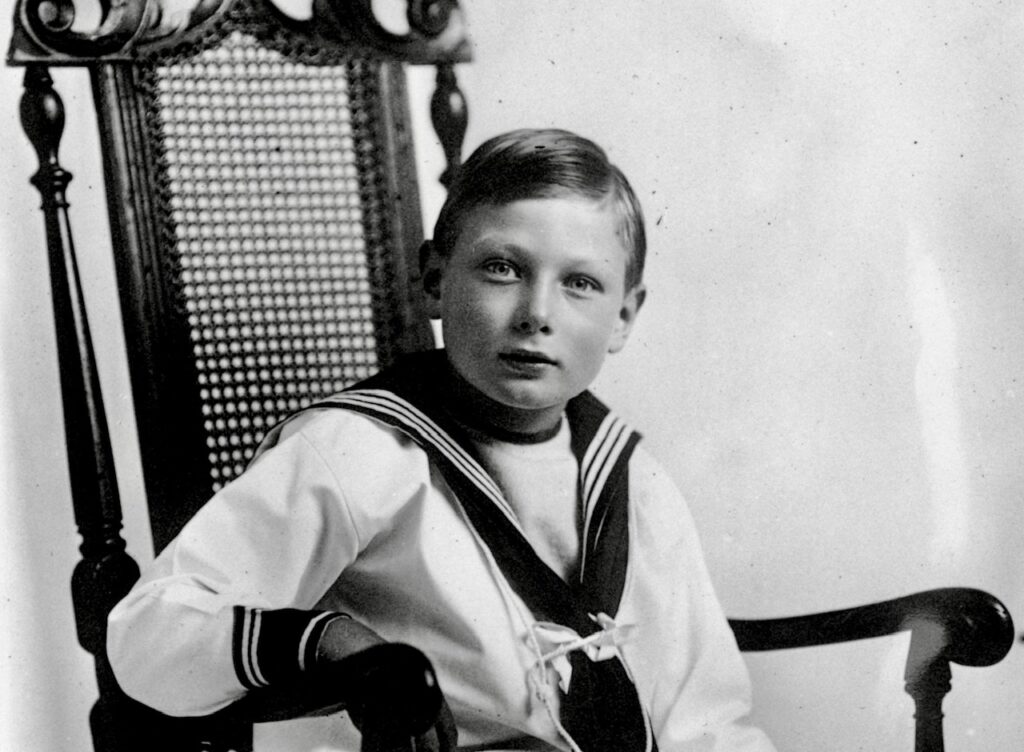

Prince John

Unfortunately, through much of history people with epilepsy were regarded as freaks. They were thought to be possessed by evil spirits, witchcraft, or demons while their illness was referred to as lunacy, the fallen sickness, or, in ancient Roman times, ‘the disease which is spit upon.’ A person with epilepsy was thought to be unclean: whoever touched him would also be possessed by a demon. By spitting, the ancient Romans tried to keep the demon away. In his book ‘The Falling Sickness’ Owsei Temkin writes that the epileptic was seen as an object of horror and disgust, not sacred as has sometimes been contended.

In the late 19th century, epilepsy was more frequently seen as a brain disease than a possession of evil spirits, but much of the stigma remained. European society was preoccupied with the idea that civilized society was degenerating due to the high birth rate of the poor. It was a time when racism and eugenics were uncontroversial. Epileptics were often put in asylums with the insane.

The story of Prince John (1905-1919) is a good illustration of how powerful the stigma of epilepsy was in those days. John was the fifth son of George V, King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions in the early 20th century. When John was found to have epilepsy (and possibly autism as well), he was sent to Sandringham House where the royal family could keep him away from public view. He died from a seizure at the age of 13. His brother, the future king Edward, wrote in a letter: “His death is the greatest relief imaginable or what we’ve always silently prayed for. This poor boy had become more of an animal than anything else and was only a brother in the flesh and nothing else.”

Cesare Lombroso: epilepsy and born criminality

Shortly before Prince John was born, one person published a depiction of the epileptic personality, so damaging that it would impact people with epilepsy for decades to come. His name was Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909). He was an Italian physician who studied criminals by measuring the shape of their skulls. Over the years he added one additional ingredient to his phrenological theory of criminality.

Lombroso stated bluntly that epilepsy is “the basis of born criminality”. “Epileptics are really more dangerous than moral mad men”, he said, “with whom they have an extreme analogy.” In earlier times people invoked evil spirits or witchcraft because they were so horrified by the sight of seizures. Now, Lombroso used the same anguish to argue that epileptics were not in control of themselves, that they were aggressive and a danger to society. Epilepsy was said to be an atavistic throwback to a primitive stage and a fundamental component of criminality.

Lombroso’s writing on epilepsy is a good example of how harmful stereotypes and illness metaphors can be. A 1954 article in the New York Times reports that many epileptics still could not migrate to the United States, teach in some public schools or marry in several states. In surveys carried out in the UK in the late 1970s and early 1980s people with epilepsy were still seen as “excitable and aggressive, and even potentially violent.” An analysis of 62 movies containing scenes of epilepsy shows that male characters with epilepsy are often portrayed as “mad, bad and commonly dangerous.” According to a recent historical review in the journal Epilepsia, “Lombroso’s theory of a strict connection between epilepsy and the criminal personality exerted a long-lasting negative influence on both medical and public opinion, and strongly contributed to the stigmatization of patients with epilepsy.”

Potassium bromide

The idea that epilepsy is associated with criminality, is but one of many myths that have been associated with the illness. Others were more clearly psychosomatic in nature. In the past, for example, it was thought that an epileptic attack could provoke the illness in bystanders. Fabricius Hildanus (1560-1634) attributed two cases of epilepsy in infants to the imagination of their mothers, because she had seen epileptics while pregnant. The esteemed Dutch physician Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) also speculated about this possibility while his pupil van Gerard van Swieten (1700-1772) thought that hysteric passion could degenerate into epilepsy. As one review article summarized, even in the 19th century, “epilepsy and hysteria were closely linked in the minds of many authors.” An excellent illustration of this is the discovery of potassium bromide, the first effective antiepileptic drug.

The year was 1857. During a meeting of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society, the president, Sir Charles Locock, mentions that he had been using potassium bromide in patients with ‘hysterical epilepsy’. This was a condition where seizures occurred mainly around the time of menstruation (what we today might call ‘catamenial epilepsy’). Like many before him, Locock thought that the illness was caused by sexual excitation. He had read a report that potassium bromide induced temporary impotence in males and wanted to see if it could also reduce sexual excitement in his female epileptics. The drug worked but not for the reasons Locock originally had in mind! Potassium bromide remained the standard treatment for epilepsy until the 20th century.

A psychoanalytic side turn

At the end of the 19th century, physicians started to get a better view of epilepsy as a brain disease. The English neurologist Hughling Jackson wrote that “epilepsy is the name for occasional, sudden, excessive, rapid and local discharges of grey matter”, an accurate description that anticipates scientific breakthroughs in the next century.

Before further progress could be made, however, epilepsy research would take an unfortunate side turn into one of the darkest episodes in the history of psychosomatic medicine. Rather than studying the mechanism of epilepsy and how it takes effect, researchers started speculating what its ultimate cause might be. Psychoanalysis became popular and the phenomenon of shell shock during WWI sparked an interest in psychogenic explanations. Alan Mcdougall, Director of the David Lewis Epileptic Colony in Cheshire, wrote in 1919: “The weirdness of some of the fits of some of the men discharged from the Army as epileptic makes prominent in one’s mind the ever-present question: Whether there is a boundary line between epilepsy and hysteria?”

A flight into unconsciousness

In the 1920s a new psychosomatic theory was formed that saw epilepsy as a ‘flight into unconsciousness’. People with epilepsy were said to be egocentric, infantile, and narcissistic and when they were no longer able to face up to the disappointments and difficulties of the real world, they retreated from reality in the form of a seizure. Ferenczi, for example, said that epileptics “take refuge in a completely self-contained and self-sufficient way of life as it was lived in the womb, that is to say, before the painful cleavage between the self and the outer world took place.” In their classic textbook “Diseases of the nervous system” Jelliffe and White write:

“The extreme egocentricity of the epileptic, his great failure to project his interests into the outer world, his tendency, therefore, to retreat further and further from reality and to revive earlier ways of finding pleasure, results in a profound regression, which, in the unconsciousness of the fit, reproduces the helplessness of the child in utero and demands the same degree of absolutely complete care.”

The greatest proponent of this view was the American psychiatrist Leon Pierce Clark (1870-1933). Clark worked at the Craig Colony for epileptics and was president of the National Association for the Study of Epilepsy. In an interview with the New York Times in 1920, he said:

“the epileptic is emotionally poverty-stricken. He cannot suffer the natural emotional experiences and strains through which every normal being has to go. He has the capacity for a certain amount of his mental experience and then he breaks. The attack is very much in the nature of a protective mechanism.”

Some of the psychosomatic literature on epilepsy shows such a strong contempt and disdain for patients, that it feels like reading a racist pamphlet filled with hatred. Clark for example stated that the epileptic personality was characterized by “egocentricity, supersensitiveness, and emotional poverty”. He wrote that “the extreme sensitiveness from which the epileptic suffers is caused entirely by the self-centered life he leads. Instead of giving himself up to the realities of life and forgetting himself in his environment, his mind dwells continually on himself.” Jellife and White write that “many epileptics are feeble-minded or more profoundly defective.” They added that people with epilepsy frequently lie and that they are lazy, suspicious, and ‘hypochrondriacal’. Ferenczi said that “the epileptic should be regarded as a special human type, characterized by the piling up of unpleasure and by the infantile manner of its periodic motor discharge.”

Epilepsy and masturbation

Others had the weird idea that an epileptic episode carried the same symbolic meaning as masturbation. “In almost all my cases”, Steckel wrote, “I have found a close connection between masturbation and epilepsy.” Greenson offers a case example where “it was clear that since the onset of the convulsions the masturbation had lost its gratifying character. It was as though the repressed fantasies were now discharged in the seizures rather than in the masturbatory act.” In their 2016 book ‘The end of epilepsy’ Schmid and Shorvonon write that “the idea that epilepsy was caused by self-masturbation was one that was widely accepted until the middle years of the twentieth century.”

Sigmund Freud also referred to it when he argued that the epilepsy of the famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1888) was psychosomatic. “It is highly probable that this so-called epilepsy was only a symptom of his neurosis” he said about Dostoevsky, “and must accordingly be classified as hystero-epilepsy – that is, as severe hysteria.” Freud came up with a theory in which a ‘strong innate bisexual disposition’, Dostoevsky’s hatred for his father, and a need for self-punishment, all, somehow, played a role in his epileptic attacks. Dostoevsky’s addiction to gambling was compared to the impulse to masturbate. Everything was connected with psychoanalytic reasoning.

In their neurology textbook, Jelliffe and White also propose psychoanalysis as a treatment for epilepsy. They explain that the therapy should “slowly lead the patient into reality by arousing his interests in things outside himself, a gradual leading away from the egocentric fixation.” They also advise “a reeducation of the other members of the family whose attitude often serves to help to keep the patient ill.”

Critique

With such strong statements, it should not come as a surprise that other experts deplored how psychosomatic thinking affected epilepsy research. James Taylor, a disciple of Hughling Jackson, wrote in 1921 in the BMJ about some unfortunate new trends in the study of epilepsy: “I have been not a little disappointed and surprised at the tendency which has lately become obvious towards an attempt to approach its explanation on other grounds than that of physical disturbance – in my opinion, a definitely retrograde movement.”

Charles Burr was more cautious when he stated: “The most recent hypothesis, that the convulsions are psychogenic in origin and are a defense reaction of the subsconscious mind against an unpleasant situation, needs much more evidence than has been brought to its support. I suspect that biologic chemists rather than psychiatrists will solve the riddle.”

Sachs was blunter and criticized Clark directly: ‘‘starting with presumptions which have not been proved, the author builds up a structure purely fantastic. Dr Clark’s personal experience is very large, but I do not think that he will be able to prove clinically that the vast majority of patients with epilepsy are homosexual, that they cannot be tempted into heterosexual fields, or that their libido is variably improper; the patient with epilepsy behaves as the average human behaves.”

Stigma

After WWII psychosomatic speculation on epilepsy disappeared from the mainstream scientific literature, but its influence on public perception might have lasted much longer. A Gallup poll asked people from 1949 to 1979 if they thought epilepsy was a form of insanity. The proportion of those who did not, rose from 59% to 92%. In a 1995 survey, nearly half believed that people with epilepsy had more personality problems than members of the general population. Similarly, a bi-monthly UK Omnibus Survey showed that one-fifth agreed that people with epilepsy have more personality problems than others. 19% thought that epilepsy was a mental health problem. A 2001 study among high school students also showed that approximately one-fifth “definitely believed that epilepsy was a form of mental illness”. In a German study from 2010, 11% agreed with the statement that “epilepsie ist eine form von Geisteskrankheit.”

Conclusion

Iranian neurologist Rajendra Kale once wrote that “the history of epilepsy can be summarized as 4000 years of ignorance, superstition, and stigma followed by 100 years of knowledge, superstition, and stigma.” It is hard to think of an illness where stigma was so damaging as epilepsy. As usual, psychosomatic medicine strengthened these harmful preconceptions, rather than disarm them.

In a future blog post, we will delve into the concept of ‘psychogenic, non-epileptic seizures (PNES)’ as an example of controversial psychosomatic theories in the present. More to come!

An overview of all articles in this series can be found at the bottom of the introductory article.

I’m enjoying reading all the articles on this subject. My eyes are getting lots of exercise doing eye-rolls at the statements “scientists” get away with.

I am enjoying this series. You write very well. I know an epileptic person for whom, as far as I know, overstimulating social situations or stress can increase frequency of seizures, i.e. person tries to manage stress because they’re epileptic, but they’re not epileptic because they need to manage emotional stress – which goes to show how one aspect of disproven theories could be confusing cause and effect,