Catastrophizing, a cognitive distortion that amplifies the perceived threat of symptoms, has been at the center of cognitive-behavioral models of pain and fatigue. In recent years, however, researchers argued that the concept has been misapplied and that it has a stigmatizing effect on patients. While some propose to rename the term, the underlying issue appears to run much deeper.

Introduction

Catastrophizing refers to an exaggerated negative mental schema brought about by (actual or anticipated) painful and negative experiences. It can include pessimistic worrying, exaggerating threats, a repetitive focus on symptoms, and a perceived inability to control the situation.

For the past twenty-five years, catastrophizing has been a widely studied topic in pain research. It is one of the most powerful psychological predictors of pain intensity and is central to the fear-avoidance model. Health psychologists believe that thinking in a catastrophic way, can make your pain feel worse and puts you at risk for chronic pain and disability.

Catastrophizing also features prominently in the cognitive behavioral model for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). As one paper explains: “This model supposes that unhelpful catastrophic interpretations of symptoms and excessive focus on symptoms are central in driving disability and symptom severity.” In two of the largest trials of rehabilitative interventions for ME/CFS, catastrophizing was an important mediator of treatment effects. In the PACE study, for example, catastrophizing explained 18 percent of the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on physical function and 12 percent on fatigue.

In the past 5 years, however, several research groups have expressed concern about the concept. While catastrophizing shows statistical associations with adverse pain outcomes, there are problems with how questionnaires have measured and implemented it. To understand these problems, we need to go back to the beginning.

Ellis and Beck: expecting the worst

The term catastrophizing was introduced and developed in the 1960s and 1970s by Albert Ellis and later Aaron Beck, two pioneers of cognitive therapy. They identified it as a distorted thinking pattern in patients with mental and emotional problems. Their treatment approach consisted of highlighting irrational thoughts so that patients became aware of them and could challenge their effects.

The first thing that stands out in reading their books, is that they used catastrophizing in situations that were clearly not catastrophic to a neutral observer. They describe patients who exaggerate adversities into something far worse than they are. Ellis described it as “The idea that it is awful and catastrophic when things are not the way one would very much like them to be.” He gives the example of a female sex partner making critical remarks about the small size of a guy’s penis: certainly not a nice situation to be in, but not a catastrophe either.

Beck’s implementation of catastrophizing focuses on seeing the most unfavorable of all possible outcomes. He gives concrete examples such as a person in a car who dwells on the possibility that the car may crash and that he will be killed. Or a guy who thinks that his girlfriend must be cheating on him because she is late for an appointment. In each case, the patient has an unrealistic and pessimistic forecast of future events. He focuses on the worst-case scenario: “a wart means he has cancer; a sudden burst of thunder means he will be struck by lightning; an approaching stranger suggests the possibility that he will be attacked.”

The migraine of Maupassant

The first use cases of catastrophizing in the chronic pain literature tested patients who were getting a dental procedure or had their arms immersed in ice water for 60 seconds. Because those pain experiences were relatively minor, it remained possible to identify catastrophic thinking.

The problems arise when catastrophizing is used in patients with a severe, chronic disease where it is less clear that patients suffer from distorted thoughts. In such cases, it is difficult to differentiate between the severity of symptoms and catastrophizing.

Consider, for instance, the following paragraph where French novelist Guy de Maupassant vividly describes his anguish during a migraine attack. In Sur L’eau he wrote:

“Migraine is atrocious torment, one of the worst in the world, weakening the nerves, driving one mad, scattering one’s thoughts to the winds and impairing the memory. So terrible are these headaches that I can do nothing but lie on the couch and try to dull the pain by sniffing ether.”

Researchers have used this passage as an example of catastrophizing because Maupassant appears overwhelmed by his pain and helpless to deal with it. But one could just as well argue that his thinking pattern is not distorted but an accurate reflection of his suffering. Perhaps the health psychologists would evaluate it differently if they could feel the pain and torment that Maupassant experienced during the migraine attack.

This is the crux of the story: catastrophizing can only be assessed in the absence of a catastrophe. A chronic illness is often a catastrophe, one that destroys careers and relationships and affects all aspects of life. Elizabeth Seng, Associate Professor of Psychology at Yeshiva University explained this quite eloquently:

“The problem is that the “catastrophe” many of our patients worry about is their reality. They worried they would not recover fully – and they didn’t. They worried that their pain would last forever and so far that seems true. Our patients rightfully feel patronized when we call their lived experience a “catastrophe,” as though it is so outlandish it will never happen. For many, they are already living it.”

The Pain Catastrophizing Scale

After identifying this first major problem, let’s proceed to how catastrophizing has been used in chronic pain research where it enjoyed its greatest popularity. The most used measurement tool of catastrophizing is the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) published by the Canadian research team of Michael Sullivan in 1995.

The PCS assesses study participants’ thoughts and feelings when they are experiencing pain. It presents them with 13 statements, which they rate on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The statements are grouped into 3 subscales that measure helplessness, magnification, and rumination. Participant do not have to suffer from pain at the time of assessment, they can just indicate how they felt when they were in pain.

Notice that the items rarely ask about pessimistic forecasts of future events or worst-case scenarios. Indeed, a common criticism of the PCS is that it deviates from how catastrophizing was originally conceptualized by Ellis and Beck. The PCS does not, for example, ask about patients’ belief that they will end up paralyzed or that they will lose their jobs.

The focus is on what the patient is experiencing in the present. This makes it difficult to differentiate between a patient with minor pain who is catastrophizing and a patient with horrific pain who is not. Take for example the statements: ‘It is awful and I feel that it overwhelms me’, ‘I keep thinking about how much it hurts’, or ‘I feel I cannot stand it anymore’. These statements could just as well reflect the intensity of pain rather than how patients think about it. Other items such as ‘There is nothing I can do to reduce the intensity of the pain’ or ‘It is terrible and I think it is never going to get any better’ might indicate how well a patient’s pain is being managed or how (un)successful treatments have been.

To put it more directly, the PCS fails to distinguish between catastrophizing and pain itself and there is some evidence to support this view. In several studies, the PCS was administered before and after participants experienced a painful stimulus such as putting their arm in ice-cold water. The catastrophizing scores subsequently increased suggesting that patients complete the questionnaire differently when they are in (relatively mild) pain. Or as one paper described it: “individuals who do not typically ‘catastrophize’ may have catastrophizing thoughts when experiencing severe pain.” The changes in catastrophizing by inducing (minor) pain are often larger than the reductions seen after cognitive behavioral therapy.

The research team of Geert Crombez took another approach. This group identified cut-off scores for the PCS, translated the questionnaire to Dutch, and adapted it for children and adolescents. But at one point they started to question the fundamentals: did the scale really measure what it is supposed to measure? It may surprise you, but this question is rarely asked in psychology research.

Crombez and colleagues formulated definitions of catastrophizing and multiple related concepts such as pain-related worrying, vigilance, pain severity, and distress. They then asked participants to assess whether each questionnaire item fit a given concept, allowing them to rate their confidence with a score from 0 to 10. Positive scores indicated agreement, while negative scores indicated disagreement. The results for the PCS showed that it did not measure catastrophizing very well. It received a mean score of less than 2, almost no better than the score for the concept pain severity. Most of the participants thought the PCS items measured worrying and distress which received a score around 6 points. Other questionnaires used to measure catastrophizing showed a similar pattern.

This would explain why the PCS provides consistent correlations with negative pain outcomes. It does not only measure an unhelpful thought pattern but also pain intensity, worry, distress, (unsuccessful) pain management, and other factors that patients know but the researchers likely don’t. Rather than providing evidence for the role of catastrophizing in explaining pain and disability these correlations signaled a problem with confounding. The questionnaire was likely measuring all of these things at the same time.

Catastrophizing in ME/CFS

The ME/CFS literature shows how easily catastrophizing can be misapplied. The condition is highly disabling but under-researched. This combination creates a high risk for symptoms to be misinterpreted as catastrophizing.

The first major study of catastrophizing in ME/CFS, for example, asked patients: ‘What would be the consequences of pushing yourself beyond your present physical state?’ Catastrophic thinking was identified by responses such as ‘total body collapse’, ‘I’d probably have a stroke and die’, and ‘I’d end up totally bedridden’. While a stroke is admittedly unlikely, the other responses may not be an exaggeration. ME/CFS is now believed to be characterized by post-exertional malaise where patients experience a setback or crash when they exceed their energy limit. In other words, some patients may not have been catastrophizing but describing what happened to them.

Most research on catastrophizing in ME/CFS used a 4-item subscale of the cognitive and behavioural responses to symptoms questionnaire (CBRQ). Patients can indicate how strongly they agree with each statement using a 5-point Likert scale (0-4). The scale originally used 7 statements of which 3 were eventually deleted (those crossed through below). Older studies such as the FINE trial used the 7-item version.

The CBRQ subscale suffers from the same problems as the PCS. Items such as ‘My illness is awful and I feel that it overwhelms me’ reflect the severity of symptoms while ‘I will never feel right again’ asks about expected prognosis. People who have disabling symptoms or who have been ill for a long time will automatically have higher scores.

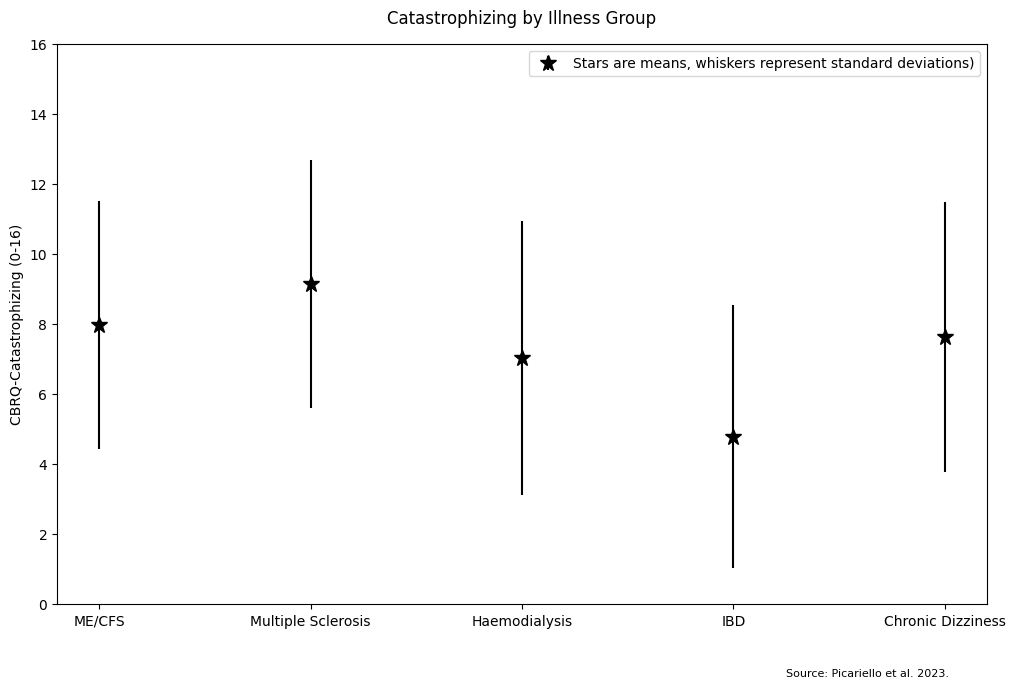

ME/CFS patients are therefore at risk of being misdiagnosed with catastrophic thinking. One study, for example, concluded that ME/CFS patients suffer from ‘unhelpful cognitive and behavioral responses to symptoms’ because they scored higher on the CBRQ subscale than asthma patients who were less ill and disabled. Comparisons with other illnesses such as multiple sclerosis, however, show that ME/CFS patients do not have abnormal catastrophizing levels.

The scores in the image above do not correct for fatigue severity or illness duration but others have. One study compared ME/CFS patients to three autoimmune rheumatic diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, seronegative spondyloarthropathy, and connective tissue disease. At first, it seems that the ME/CFS patients had (slightly) higher catastrophizing scores on the CBRQ subscale, but after controlling for fatigue and illness duration the opposite was true. Patients with rheumatic diseases had an average score of 8.84 points, significantly higher than the 7.76 points observed in ME/CFS patients. Whatever catastrophizing scales are measuring, the scores do not seem abnormally high in ME/CFS patients.

Is it just about the name?

In 2023, researchers from Stanford University published the results of a large survey where pain patients and caregivers could indicate what they thought about catastrophizing. The replies show that patients often feel blamed and accused of exaggerating their symptoms. Here are some of the quotes from the study:

“On an emotional level, I find it a bit demeaning and blaming. It carries the implication that my pain is imaginary, or that I’m exaggerating it.”

“I find it very victim blamey to use pain catastrophizing, and that it is often weaponized against disabled people, especially those who don’t have a clear medical explanation for their pain“

“It implies that the patient could lessen their pain if they’d only try hard enough not to think about it […] When you have severe chronic pain, the kind that disables you, it’s all encompassing. It affects everything you do, your relationships, etc.“

Several researchers have proposed to rename catastrophizing to something that is less stigmatizing to patients such as ‘pain-related worry’. A new questionnaire developed to measure catastrophizing has been renamed to the ‘Concerns About Pain (CAP) Scale’. But the problem appears to lie deeper than the name. Most respondents to the survey were not as concerned with the label per se but rather the impact they felt it had on their experiences with clinicians.

Researchers have used a questionnaire that measures pain intensity, prognosis, worry, and distress and have called it pain catastrophizing, priming clinicians that patients often exaggerate their pain when this may not be the case. As several patients pointed out, what needs to change is the concept of catastrophizing itself:

“If you are only looking for a more palatable term for the same condescending mind set, what is the point? Do you think we will be less offended when you treat us the same as before but use new nomenclature? The attitude needs to change. The patient needs to be believed. Fear of pain and actual pain are completely different things and should never be lumped together.”

“How about not labeling it as a medical problem? It may be a normal reaction to an abnormal situation rather than a pathology. If a patient has untreated pain that is the primary source of disability, maybe we shouldn’t see that as a pathology of the patient but as a failure in treatment.”

“Worrying about future pain or consequences of your future pain when you live with a lifelong disease that causes unrelenting pain is NORMAL. There’s no need to medicalize someone’s pain experience or turn it into a diagnosable psychological disorder.”

In an interview, patient advocate Andrea Anderson who was involved with the Stanford project explained that pain catastrophizing is increasingly used to deny care to patients with intractable pain. “Over the last few years, as the opioid crisis became a real issue”, she said, “we started to see patients removed from pain medications, and one of the ways that physicians would justify this to patients is to say that they didn’t really have pain – they were catastrophizing.”

The Belgian team of Crombez and colleagues have taken the position that pain catastrophizing cannot be assessed by self-report questionnaires. It requires contextual information, and expert judgment, which cannot be provided by self-report questionnaires. While others have cautioned about not throwing out the baby with the bathwater, it should be noted that most studies on catastrophizing have been cross-sectional (i.e unable to show causation) and are of low quality (as rated by this review).

Hopefully, there will be more critical investigations of how constructs like catastrophizing can be misused to label patients’ symptoms as unhelpful cognitive responses. In future blog posts, we aim to look at somatization, kinesiophobia, and self-efficacy, terms that are often used in the ME/CFS literature and that suffer from similar problems.

Oh man! I was given questionnaires to fill in by my local M.E/CFS clinic as part of a PACE derived treatment which specifically aimed to dissuade ‘catastrophizing’. Some of the questions I had to answer are mentioned in this article almost verbatim. I was told to do these every morning before increasing my activity week on week….. I went from moderate to bed/housebound and remain so nearly a decade later. Sadly I approached the treatment with nothing but positivity and enthusiasm, the resulting catastrophe was not in my head or of my own making…..

Very sorry to hear this and thanks for sharing your story. I’m afraid that here are many cases like yours. We sincerely hope that research methods will improve so that new patients don’t have to go through all of this.

I wish more of these ‘researchers’ could LIVE the diseases they denigrate.

The problem is that when they get, say, long covid, THEIR OWN PEERS disparage what they find out – and they’re no help to the rest of us, either!

And newbies are SO needy!

I didn’t realize there was so much on the ridiculous idea that we are catastrophizing – that we are exaggerating our pain because of some sick idea that we GET something from so doing, or that we LIKE being this way.

The frustration patients have with this kind of reception from the ‘helpers’ – starting with Freud – having our legitimate problems and concerns be declared not WORTHY of real attention and help – is hard to express sufficiently, which is partly why I’m writing the Pride’s Children trilogy – I challenge you NOT to believe the main character with ME/CFS when you’ve lived in her skin for as long as GWTW (along with the other two main characters).

Keep doing what you’re doing. Even if it KEEPS making us mad. The anger is as real as the disease.

Dear Alicia,

Thank you. For using precious energy to write such an empowering post.

It’s enough we often use our all to survive on a daily basis, having to battle the health system plus out dated philosophies makes it so much harder. Proud of you Alicia

Sara

The reason this term became associated with ME/CFS is that CBT was promoted as a treatment for it. You wouldnt treat cancer or MS with CBT so why the hell did CBT become associated with ME.

ME is like diabetes. Just like sugar is ok in moderation but dangerous in larger amounts so exhertion is ok in moderation but dangerous in larger amounts. You wouldnt give CBT to a diabetic and tell them to stop catatrophising about the effects of sugar would you?

Barbara Ehrenreich has a fantastic book on the toxic influence of positive thinking, called Smile or Die. While this is specific to her experience of breast cancer and the relentless aggressive linking of positivity to survival, I think there is an enormous amount of information and history about this fallacy that would resonate with the M.E experience of the pushing of CBT and patient blaming.

Recommended reading, if you can do of course.

Thanks for the suggestion Kat. I think toxic positivity and perhaps also the concept of ‘self-efficacy’ might be enough material to devote a separate blog post on in the future.

I have a (very offensive) philosophy related to this:

When a practicing physician dismisses the symptoms and history of the patient in front of them, substitutes a disinformation narrative which came from a special interest, and proceeds to diagnose and treat the disinformation narrative…

I don’t know what they’re doing

but it’s not practicing medicine.