In this first of many blog posts on the dark history of psychosomatic medicine, we take a look at multiple sclerosis (MS). Although we found little evidence that the disease itself was once viewed as psychosomatic (except for some marginal papers), there are strong indications that many female MS patients were incorrectly labeled with hysteria in the past. Today, MS symptoms are still frequently dismissed as psychosomatic before patients receive the correct diagnosis. Lastly, we examine a psychosomatic model of MS fatigue that bears many resemblances to the contested cognitive-behavioral model of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Selma Blair and Jacqueline du Pré

In October 2018, American actress Selma Blair revealed that she has MS during an emotional interview on ABC news. MS is a chronic disease where the immune system damages the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibers of the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves. It causes disabling fatigue and various neurological symptoms including muscle weakness, dizziness, unsteady gait, and blurred vision. Symptoms can wax and wane and the progression of MS is often characterized by relapses and remissions.

Blair said that she would get so fatigued that she needed to pull over to take a nap after dropping her son off at school, just a mile away from their home. She struggled without knowing what was happening. Blair revealed she had symptoms for years but was never taken seriously by doctors. She cried when she finally received the diagnosis of MS.

Something similar happened 45 years earlier to cello player Jacqueline du Pré. Du Pré was one of the most talented cello players the world had ever seen (we really like this performance of her) but unfortunately, her career was stopped short because of MS. She suffered from blurred vision and numbness which made it difficult to perform. Before her MS diagnosis in 1973, Du Pré’s symptoms had been ascribed to various psychosomatic causes such as mental stress, adolescent trauma, unconscious resistance, and hysteria.

MS was not seen as a psychosomatic illness

Although it is sometimes stated that before the discovery of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) MS was seen as a psychosomatic illness, we have found little evidence for this. We have skimmed several books on the history of MS (for example this, this, this and this one) and found little mention of such views.

Some researchers tried to come up with a psychosomatic theory involving stress, oedipal fixations, or an MS-prone personality that was emotionally immature and hysterical. Langworthy and colleagues, for example, write that “one must consider the possibility that conversion hysterical symptoms may ‘jell’ into organic changes characteristic of multiple sclerosis.” We even found a relatively recent paper from 2002 which speculates that “MS may be the psychosomatic consequence of early childhood trauma in the form of unsuccessful bonding processes.”

The attempts were certainly there, but they seem to have failed at gaining much influence. The history of MS and the accounts from physicians and patients we reviewed suggest that MS was always considered a serious neurological disease. If MS symptoms were deemed psychosomatic, it was not because of a diagnosis of MS but – as the cases of Blair and Du Pré indicate – because patients struggled to receive such a diagnosis.

Thought to be more common in men than in women

MS was described by various physicians in the 19Th century but it only started to receive clinical recognition after the French doctor Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) highlighted its most characteristic features. Charcot differentiated MS from Parkinson’s and neurosyphilis and described clinical signs and pathological features that helped other physicians to recognize the illness.

The problem was that those neurological signs only appeared in more advanced and severe stages of MS. For this reason, physicians initially thought that MS was rare and that people only had a few more years to live after the diagnosis. They were overlooking the vast majority of patients.

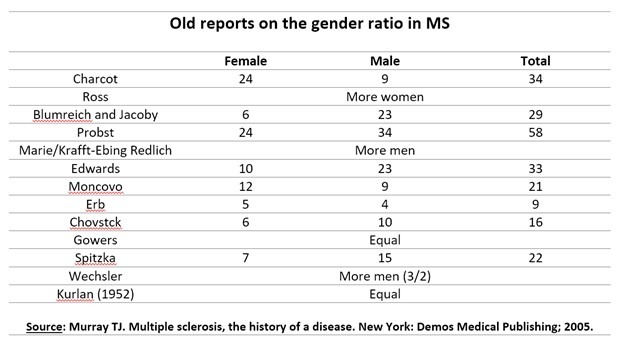

A clear indication of this is the sex distribution of the MS patient population. Although opinions differed, most researchers in the early 20Th century thought MS was more common in men than in women. The Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease (ARNMD) stated in 1921 that MS affected men more than women by a ratio of 3 to 2. Current knowledge indicates that it is the other way around: women are approximately 3 times more likely to develop MS than men.

Confusion with hysteria

What happened with female MS patients in those early days? It seems that they received other diagnoses and that hysteria was a popular alternative. Thomas John Murray, for example, writes in his book on the history of MS that “there are many cases in the early literature of MS in which the case presented was diagnosed in life as “paresis” (syphilis) or hysteria, only to exhibit characteristic changes of MS at autopsy.”

A good example of this can be found in a discussion from 1917 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). One physician noted that “The differential diagnosis between multiple sclerosis and hysteria is often difficult to make. Many apparently hysterical cases turn out to be multiple sclerosis.” Another doctor agreed and wrote: “One case I considered hysteria until I found Babinski’s sign, which is never found in hysteria.” A third physician also stated that many are forced to revise their diagnosis of hysteria because of increased understanding of MS. He highlighted that “the characteristic striking remissions after very grave symptoms are misleading. This would suggest hysteria, but is, after all, a characteristic of this disease.”

Difficulties before diagnosis

Such mistakes diminished as knowledge and understanding of MS increased. Diagnosing MS remained difficult, however, because the illness often starts with nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue or neurological symptoms that come and go. As the American neurologist and MS-expert Charles Poser noted:

“It is extremely common for MS patients to have symptoms which may sound bizarre to an inexperienced physician because they fail to conform to anatomical boundaries or physiological concepts, they may be extremely transient, lasting for no more than minutes or seconds, and most importantly cannot be confirmed by objective findings.”

Poser remarked that in the early stages of MS, symptoms can be similar to those of ME/CFS. Before diagnosis, MS patients frequently report that their symptoms are not taken seriously or mistaken to be the result of stress or anxiety.

Surveys on patient experiences were quite rare in earlier times, but we were able to find an interesting study conducted by David Stewart in San Francisco in the years 1975 to 1977. Stewart did in-depth interviews with 60 patients and their family members. It took an average of 5 and a half years before patients were correctly diagnosed. In that long period before diagnosis, patients frequently said that their symptoms were dismissed as psychosomatic or ‘all in the mind’. One patient reflected the views of many when she stated:

“I went to seven or eight doctors In less than two years. […] They’d usually just say that my problems were normal for a woman my age (25) and things like that. And I’d get really uptight because they would just give me a valium and not try to find out what was really wrong. Some of them thought I was going off my rocker. They thought I was imagining the problems.”

The authors explain that this had a damaging influence on how friends and family looked at their illness: “Compared with the patients, relatives and friends accepted the physicians‘ diagnoses much more frequently and viewed the patients’ conditions as mild physical or psychosomatic illnesses. As a result, the patients had as much difficulty convincing their relatives and friends that they really were sick as they did their physicians. When they complained about their symptoms or took it easy on days when their symptoms were particularly severe, they felt that others viewed them as hypochondriacs or as malingerers.”

One patient explained this experience as follows:

“Other people think you’re crazy when you’re always complaining about strange things and the doctors can’t find nothing wrong. I know my husband and most of the rest of them thought it was all in my head. They usually wouldn’t say that to my face, but I knew what they were thinking… When I’d say something to my husband, he’d say all you do is complain, you’ve always been a complainer – so I quit complaining.”

When patients ultimately received the correct diagnosis, it felt like a relief (some were afraid they were dying). One patient noted: “I could also finally say ha-ha to all these people who thought it was all in my head.”

Same problems after MRI scans

Those were the experiences of MS patients in a time before MRI, which only came into use in the 1980s. MRI scans can provide objective evidence of damage in different areas of the central nervous system. Although they certainly help in making the diagnosis of MS, MRI scans aren’t sensitive and specific enough to base diagnosis solely on this information. Doctors still have to take into account the clinical history and rule out other possible explanations for the symptoms. Diagnosing MS patients at an early stage, therefore, remains a difficult task.

One study states that “The pre-diagnosis period, whilst symptoms are being investigated and the cause is uncertain, can be particularly stressful, and in some cases, symptoms may not be indicative of MS; practitioners may suspect other causes, for example, psychogenic explanations.” This suggests not much has changed since the report by Stewart in the 1970s. In another recent study of MS patients, “the women interviewed expressed that when they sought a diagnosis they were not believed or were ‘fobbed off’ with a psychosomatic reason.” A third study on the illness experiences of MS notes that: “When a few sought medical assistance, they were told that their symptoms were psychiatric, but they were not offered a referral to a psychiatric consultant. When some patients said they felt a strong and unreal fatigue, people only smoothed things over by saying, ‘These days everyone is tired.’”

The psychosomatic model of MS fatigue

In summary, it seems that (mostly female) MS patients were incorrectly diagnosed with hysteria in the past and that in the pre-diagnosis stage MS symptoms are still frequently dismissed as psychosomatic. There is, however, a third story that needs to be told in this brief overview: the recent efforts to create a psychosomatic model of MS fatigue.

Because fatigue in MS patients is poorly understood, some researchers have argued that it is maintained, not so much by biological factors or disease activity, but by incorrect thoughts and behaviors. As one paper states: “the cognitive-behavioral model’s main assumption is that fatigue is not perpetuated or worsened by disease severity or associated symptoms, but by the patient’s interpretation of these symptoms.”

The model states that if an MS patient experiences fatigue, she might interpret this as a sign of pathology, of her disease getting worse. She might think that she has no control over this fatigue and that it means that there must be something terrible happening to her body. Researchers refer to this as ‘catastrophizing’ or ‘catastrophic (mis)interpretations’ of MS fatigue. Such thoughts are believed to lead to worry, increased resting, and reduced activity. This, in turn, can result in deconditioning, poor sleep, anxiety, and depression which all help to perpetuate the fatigue. As a treatment, the model proposes cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) to challenge these unhelpful cognitive interpretations and behavioral responses to symptoms.

To ME/CFS patients this might all sound very familiar because it is, in essence, a copy-paste of the cognitive-behavioral model for ME/CFS (some of the authors, such as Rona Moss-Morris, are the same). Following criticism that this model isn’t evidence-based and that it incorrectly blames ME/CFS patients for their symptoms and disability, many healthcare institutions are now changing course and approaching the illness differently. It remains to be seen if this will have any influence on the popularity of the model for MS fatigue.

Do you have interesting links or information on the psychosomatic history of MS that we need to take a look at? Feel free to post them in the comments below. In the upcoming blog post, we will examine the psychosomatic history of asthma. If you would like to receive a notification each time a new blog post appears, you can enter your email address in the ‘Subscribe’ section below.

An overview of all articles in this series can be found at the bottom of the introductory article.

Nice review. I have seen some saying that was called ‘fakers’ disease’ Did you come accross that term being used, and – if so – what is the original source?

Thanks. No sorry, didn’t come across the term ‘fakers’ disease.