This week, the results of FITNET-NHS, the biggest randomized trial of children and adolescents with ME/CFS, were published. The study found that remote cognitive behavioral therapy is unlikely to be cost-effective.

A Dutch invention

FITNET-NHS is a randomized trial of FITNET, a form of online cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The intervention was developed in the Netherlands by Dr. Sanne Nijhof at the University Medical Centre Utrecht. It aims to challenge unhelpful thoughts about fatigue and encourage patients to reduce sleeping time and increase their activity level. The intervention was designed for children and adolescents and is delivered in a web-based format with video calls and an online information portal.

In 2012, Nijhof and colleagues published the first trial of FITNET in the Lancet. The results were incredible: 63% of children in the FITNET arm recovered at 6 months compared with 8% in the standard medical care arm. The findings received much media attention but were later questioned and criticized. A long-term follow-up showed that the control group caught up and that there was no longer a significant difference between the two groups.

FITNET-NHS was created to test the effectiveness of FITNET in the British National Health Service (NHS). This ambitious study was set up in 2016 and is led by Esther Crawley at the University of Bristol. A BBC article described it as a “Landmark chronic fatigue trial” that could treat two-thirds of patients. Hopes were high, as the trial received 1 million pounds from the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

The trial originally aimed to recruit 734 participants, but because of recruitment problems, this target was reduced by half. Eventually, only 314 participants aged 11-17 were randomized to receive either FITNET-NHS or a control intervention named ‘Activity Management’. Both interventions were delivered remotely and lasted 6 months.

Non-blinded with subjective outcomes

Before discussing the main results, we should highlight some important caveats. Because the intervention requires close contact between therapist and patient, neither was blinded to treatment allocation, as is normally the case in medical trials. They both knew what intervention the trial was testing and who was receiving it. This knowledge might have influenced expectations and how patients reported their symptoms. FITNET-NHS participants also received four times more consultations than patients in the control group.

This might not be a major problem if the trial used objective outcomes that are unlikely to be influenced by expectations. But FITNET-NHS only used questionnaires. This combination of lack of blinding and subjective outcomes creates a high risk of bias. As the authors explain: “The main limitation is our inability to blind participants and their families to their intervention allocation, hence reporting bias may affect the patient reported primary outcome.”

It’s a real shame because it means the trial is unable to tell us much. If the FITNET group reports larger improvements than the control group, we can’t know if this is due to the treatment being effective or the various biases discussed earlier. Despite its price tag and large sample size, the evidence provided by FITNET-NHS is very limited because of this flawed trial design.

With this caveat out of the way, let us now look at the main results.

Primary outcome not clinically significant

The primary outcome of the trial was physical functioning measured after 6 months with the Short Form Health Survey (SF-36). FITNET outperformed the control group, but the difference was only 8.2 points (95% CI: 2.7 to 13.6), lower than the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) of 10 points. The MCID was determined by the same Bristol research group (Crawley and colleagues) and used in the sample size calculation for FITNET-NHS. Unfortunately, the abstract and summaries of the study do not mention that the primary outcome difference was not clinically significant.

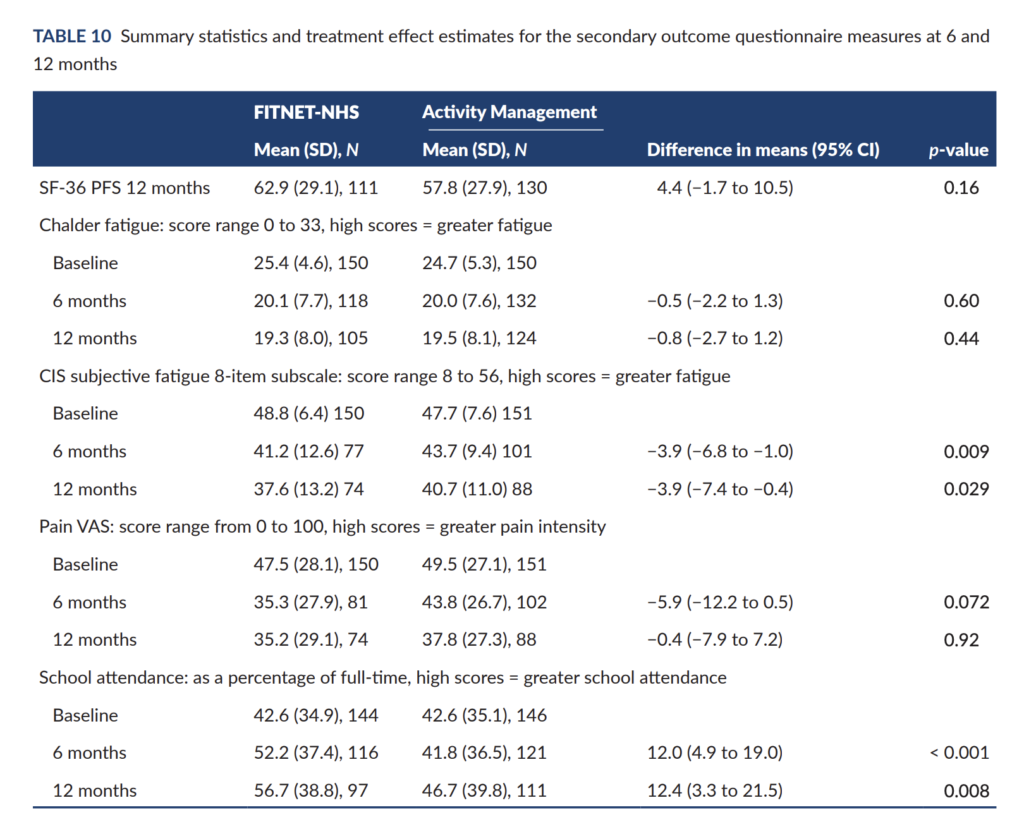

At the 12-month assessment, the control group had largely caught up, and the difference was reduced to 4.4 points (95% CI: −1.7 to 10.5). Most secondary outcomes, including fatigue, pain, or general improvement, also showed no consistent difference between the groups (see Table 10 of the report, reproduced below). The main exception is self-reported school attendance, which was approximately 12% higher in the FITNET-NHS group.

Quality of life

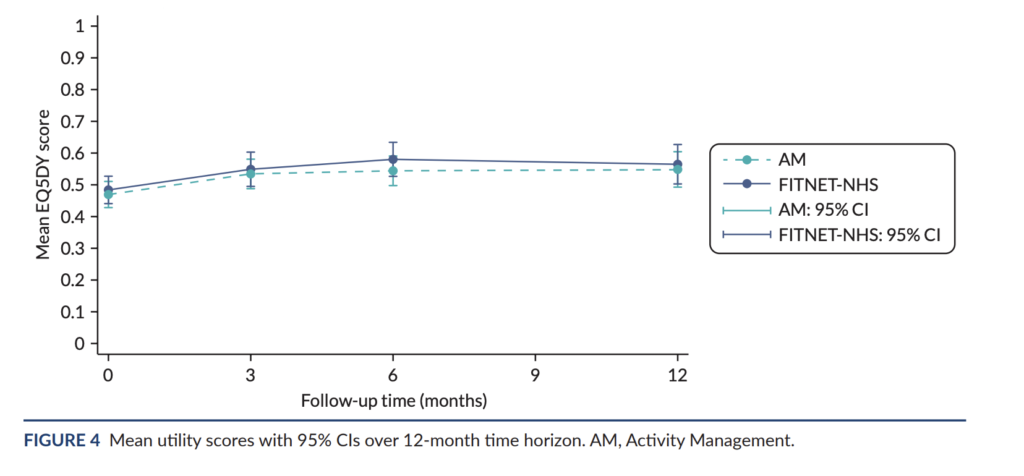

Another important outcome is quality of life, as this was used in the cost-effectiveness calculation. The authors used the EQ-5D-Y questionnaire to assess quality of life and convert these scores to quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Unfortunately, the difference between FITNET and the control group was very close to zero: 0.002 (95% CI −0.040 to 0.045). This was the case at all assessment points. FITNET did not improve quality of life.

These null effects provide more reliable evidence because the biases we discussed earlier would inflate differences in favour of the FITNET group. They would not explain a lack of difference.

Cost-effectiveness

The authors also assessed cost-effectiveness, although most healthcare costs were self-reported by parents. On average, FITNET-NHS was roughly £1000 more expensive than the control intervention, and it did not result in NHS savings elsewhere during the 12-month study period. None of the statistical analyses found FITNET to be cost-effective. The authors write that FITNET-NHS “is expensive and is unlikely to be good value for money.”

Sensitivity analyses and subgroups

The study also includes sensitivity analyses to test if some subgroups did better or worse than others. But this does not seem to be the case. The effect on physical functioning, for example, was similar for patients who met the new and stricter NICE criteria for ME/CFS. There was also no evidence that the effect of the intervention was due to the treatment of comorbid anxiety and depression (although the trial was underpowered to properly test this hypothesis).

Harms and concerns

Those are the main results but there are some other notable things about the trial worth noting.

The control group, ‘Activity Mangement’, for example, is said to be much like pacing even though its description is more similar to graded activity with statements stuch as “participants were encouraged to increase activity until they were able to do up to 8 hours of cognitive and physical activity a day.” In essence, the trial compared one graded activity program with another. There was no third arm that tested a different approach.

The current NICE guideline on ME/CFS no longer recommends these graded activity programs due to low-quality evidence and reports of harm. In the FITNET-NHS trial, about 25% in both groups showed evidence of worsening condition during the 12-month study period. 61 participants withdrew from the intervention compared to 12 in the control group. In addition, 28 participants in FITNET reported on one or more adverse events or serious adverse events compared to 18 in the activity management group.

Another notable figure is that only 37.5% of the FITNET-NHS group completed 80% or more of the expected modules/sessions compared to 78% in the Activity Management group. It is unclear why so many patients did not complete the FITNET program.

The authors conducted interviews with participants, parents, and therapists and these describe the intervention as useful but also ‘pushy’, ‘strict’, ‘regimented’, and hard at first. Some of the statements highlight problematic aspects of the intervention with children being pressed to recover and a chapter for parents on “stop asking your child how they are”. One therapist explained: “The platform can say in black and white and I think in capitals in some places, if you don’t get your sleep sorted you’re not going to get better, in places where it is really quite like if you don’t do this you’re staying ill. You have to do this you need to.” Another therapist noted how FITNET is more assertive than other activity management programs, saying: “…Once someone’s on the road to building up, then it feels like, okay, we’re getting there, whereas FITNET-NHS kind of takes it to… are you actually recovered yet?”

Conclusion

The results of FITNET-NHS show that this approach does not help patients recover or improve their quality of life compared to more simple activity management. While the improvement in self-reported school attendance is interesting, it could also be explained by various biases introduced by a problematic trial design. It seems rather cruel to tell children that they themselves are preventing recovery through their unhelpful thoughts and behaviors when this may not be the case. Perhaps the value of the FITNET-NHS is in showing that this is not the way forward.

If it has ‘Esther Crawley’s’ name associated with it, we know that it will be biased and the statistics will be ridiculous and untrue – IIRC, she is one of the proponents/supporters of the thoroughly disproven PACE trial. See all of Dr. David Tuller’s posts on Virology blog.

Don’t let her near any children you love. Or any at all.

Yep. History is going to deliver a very harsh judgement on Crawley and all those who supported and protected her and her shitty treatment of children from accountability.

Well done again on another excellent blog post.

Joan Crawford and I also had two letters published in the Lancet in reply to the original (Dutch) FITNET study:

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61324-5/fulltext

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)61325-7/fulltext